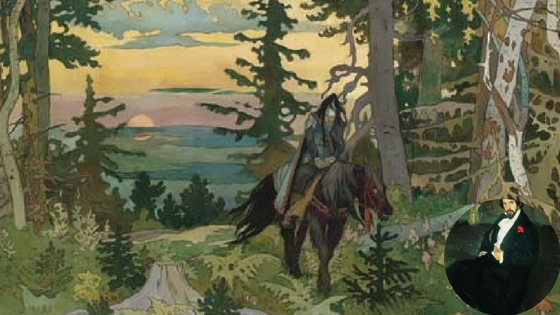

Ivan Bilibin was born on the 16th of August 1876 [O.S 4th August], in Tarkhova, near St Petersburg. Bilibin was a prolific illustrator, set and costume designer. Even if you haven’t heard of his name, I would be surprised if his art didn’t ring a bell. Bilibin was influenced largely by Art Nouveau style. His artwork is most commonly associated with Russian fairy tales. Even today, the chances of you buying a Russian fairy-tale book illustrated by him is high. Such was the influence of his art, it is arguable that Bilibin’s style has come to quintessentially define our perceptions of what Russian folklore art is.

Bilibin first studied in Munich at the Anton Azbe Art School. There, he was influenced by the Art Nouveau movement that was sweeping Europe by storm. When he returned to Russia, he studied under Ilya Repin, the great Realist painter. In 1899, Bilibin gained national renown when he released a series of illustrations for Russian fairy-tales such as The Firebird and the Grey Wolf and The White Duck. The series propelled him into a career of illustrations, set and costume designs. His creative flare was further developed during a trip to Russia’s northern territories between 1902 and 1904. The Russian north is a great expanse of endless birch and pine forests that stretches across the vast northern steppe. For Bilibin, his time spent in the north must have harked back to an old, forgotten Russia; where a way of life, traditions and old stories remained largely unchanged.

At the turn of the century, there was an intense feeling of historical nostalgia among the intellectual classes in Russia. Before the revolution, a highly politicised movement of ‘Russification’ swept across the Empire. Buildings, such as the famous Church on Spilled Blood were designed in homage to old architectural and artistic styles of old Russia. This romanticised period of creative design may have influenced Bilibin. Bilibin found himself between two schools of art; one that symbolised tradition, and one that emphasised artistic experimentation. His drawings and set designs certainly evoke this feeling of historical nostalgia. For the most part, his drawings depict scenes from famous Russian fairy tales. Many these are set in the dense birch-tree forests of Northern Russia. He depicted his characters in elegant, traditional Russian costumes. At the same time, however, the Art Nouveau style heavily influences his illustration. Vibrant, but at the same time muted, his illustrations are made of basic, solid colours. The drawings are simple, but elegant, sometimes bursting with visual liveliness; the attention to the small details is clear. They are characterised by soft, curved shapes and lines typical of Art Nouveau style.

Bilibin designed the sets for many ballet and opera performances. One notable mention is the premiere production of Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov’s opera The Golden Cockrell in 1909. After the Revolution in 1917, Bilibin fled abroad, first to Egypt, and then to Paris. Like many emigres, he longed for homeland, but it was not until 1936 before he returned. Settling in St Petersburg, by then renamed Leningrad, Bilibin lectured at the Russian Academy of Arts, until 1941. He died in 1942 of starvation during the Siege of Leningrad, having refused to leave the city. He was buried in a collective grave.

Bilibin’s drawings are still popular to this day. Because his illustrations depict traditional Russian folklore stories with a more experimental artistic form that is perhaps more familiar to us now, his legacy is one that continues to influence our perceptions of traditional Russian culture. The prevalence of his drawings among foreigners and Russians alike seventy-six years after his death is testament to his talent.

Students will be happy to learn that the Russian Government has today announced plans to make Russian language easier in an effort to simplify greater international engagement. …

In a previous post, we revealed that Russians don't really say “na zdarovje” when they toast. While the phrase has been popularised in English language media – and a lot of Russians will nod politely and clink glasses with you if you use it – it’s not something a native speaker would ever…

Improve your Russian while working as an expat? Mission possible! …

What could be a better way for Russian immersion than reading, especially when you read the books that you find interesting and that can give you a better idea of the culture of Russia? Co-founder of Liden & Denz, Walter Denz shares his experience on how reading Russian literature can improve your…

Learning a language is hard. Keeping it when you don't have classes is even harder. So this article is not about how to learn Russian, but how to maintain your Russian. …

I love Russia. I have been living in St. Petersburg for almost two months, and after travelling all around the world it feels like I have finally found a place where I would see myself settling down. The inexorable beauty of the streets, the architecture, the importance of art and culture, the water…

Oh, the Russians! I was recently watching the last season of Stranger Things and, to my surprise, Russians are quite present there. For those of you who might not be familiar with the TV series, it is set on an American town during the 80s. And what do we recall from those times? The unique fashion…

In an attempt to improve my Russian skills, I decided to start watching a TV series in Russian. After thorough research, the result of which you can read on my post about how to learn Russian with Netflix, I decided I would start watching Fartsa. I am no sure of how much Russian I am learning thanks…